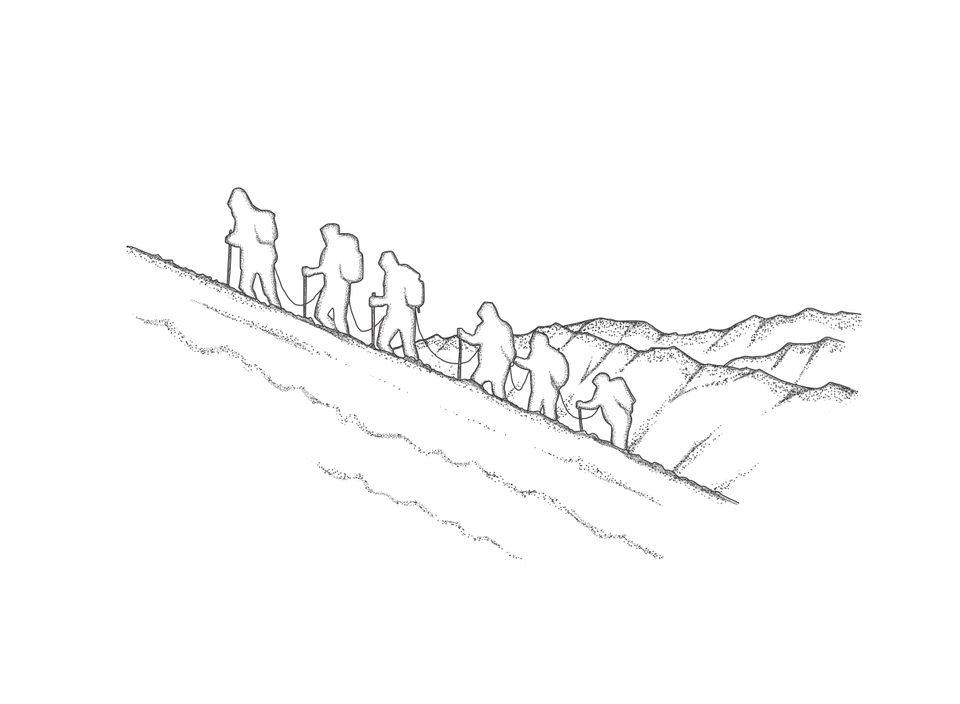

Roping up

For Scott.

When crossing glaciers or steep terrain, climbers attach themselves at equal intervals to a shared safety rope. If one climber falls, the others must break the descent, or fall with them. Every movement on the rope must take into account the needs of the climber in front and the one behind. Too much slack risks a crevasse fall that cannot be stopped. Too little inhibits movement altogether.

Roping up asks us to entrust our safety to others, and to keep others safe. We must overcome our fears about our team members. We must also overcome our doubts about ourselves. Into Thin Air, Jon Krakauer's account of an ill-fated expedition up Mount Everest in 1996, includes a straightforward appraisal at base camp of the strengths of his team. They were not the weakest climbers on the mountain that year, by Krakauer's reckoning. But they were not the strongest either. Later, eight of them would die.

Roping up requires a shift in identity, and perspective. We sublimate our most vital needs into those of the team. As individuals, we become more vulnerable to missteps from others, and gain protection from our own. Collectively, we become safer. We also gain a sense of belonging. We forget our own needs, and become connected to a larger whole. In losing ourselves, we find transcendence.

To rope up is to commit oneself fully to a team. In that commitment, there is magic. In 1951, the Scottish mountaineer Bill Murray joined the British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition as its deputy leader. The expedition assessed different ascents, paving the way for a second British expedition in 1953―the first to reach the summit. The 1951 expedition took two months, and reached the floor of the Western Cwm glacial valley, at 20,000 ft. Murray writes this in The Scottish Himalayan Expedition:

“Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one's favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamt would have come his way. I learned a deep respect for one of Goethe's couplets:

Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it.

Boldness has genius, power and magic in it!

Writing about climbing ropes reminded me of the importance of safety to the functioning of high-performing teams. There is Google's finding that the presence of psychological safety on a team is the clearest predictor of team performance. There is Patrick Lencioni's The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, which are (in order): absence of trust, fear of conflict, lack of commitment, avoidance of accountability, and inattention to results.

There is also Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs, which posits a theory of human motivation based on the fulfillment of a pyramid of needs, with new needs arising in us only after we have satisfied more basic needs. The needs are (in order): physiological, safety, belonging and love, esteem, cognitive, aesthetic, self actualization, and transcendence.

Each week I explore a life metaphor that has touched me in my coaching. Subscribe to get my scribblings every Sunday morning. You can also follow me on Medium, or on LinkedIn. Feel free to forward this to a friend, colleague, or loved one, or anyone you think might benefit from reading it.