Patience

Patience is what the world requires of us. We spend our lives waiting for things we cannot control—traffic, queues, a raise at work, the next stage in our lives. To be patient is not to acquiesce to our suffering, but to endure it well.

To find patience is to learn how to moderate the sorrow of life—our disappointments, our failures, separation, sickness, death. It is to understand that anguish and grief are bodily phenomena that take time to work themselves through us; and that even when our hearts are broken we can allow ourselves the solace of companionship, nature and prayer.

Patience is a habit of mind. When we commit to practice, we strengthen the patience in us. We become more patient by noticing what causes boredom, frustration or anger to arise in us; by staying with our discomfort; and by finding opportunity and meaning in our suffering.

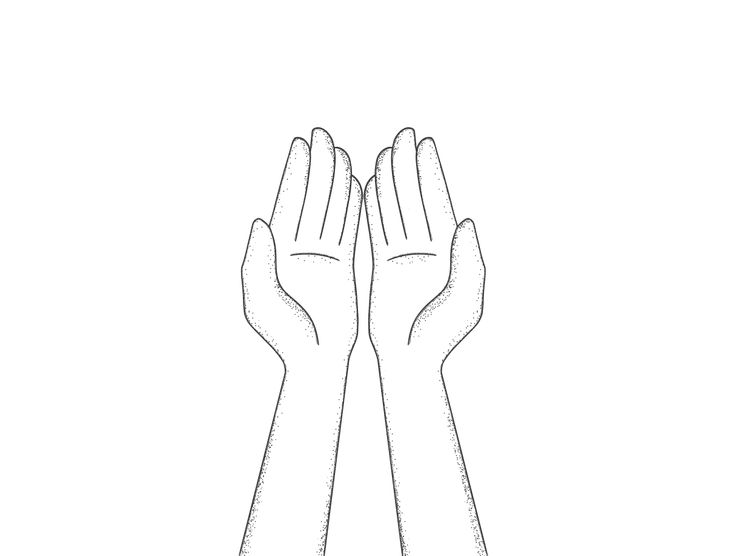

Patience is a gift. It helps us to stay calm and persist through adversity. For all our delusions of control, life mostly happens without regard to our efforts. Patience allows us to receive the time we are given, as a gift. In finding patience, we welcome grace into our lives. As we become more patient, we grow in acceptance, gratitude and understanding. Patience brings us closer to love.

Why do we live such busy lives? What do we think we will gain by squeezing more and more out of our over-scheduled days? More happiness? More contentment? More fulfillment? More meaning? More peace? How do our lives become richer as we rush through one part of the day to get to the next?

Impatience is everywhere. When we shop, we expect instant delivery. When we invest, we want instant returns. When we protest, we expect instant results. Media saturates our lives, clamoring for our attention. Technology lets us do more with less, faster and faster. We no longer have the time for persuasion or understanding. We hire and fire rather than train and coach. Our politics have become hand-to-hand combat.

Perhaps we believe that if we buy enough stuff or pack in enough experiences we will somehow avoid the pain of life altogether. Perhaps, in our unhappy age of abundance, we have come to believe that suffering is optional.

For the most part, the modern project is just year after year upping the dial of acceleration. We see it with technology, within social change, and then also with just the pace of our lives. Busyness does give us an immediate kind of sense of living a full life, but it is a kind of a hollow fullness, I think, which is what this whole thing is about. It's that stripping time of any of its sacred weight, so it can go fast. But then when you're forced to slow down a little bit, you realize that there's a kind of frightening hollowness to it. If we can have this form of action of what it means to be connected to something, of hearing the world speak to us again, a feeling drawn into something, that's a kind of form of waiting that is really deeply generative and connects us to something. That's kind of where I want to go with this. It's to recover the sacredness of time.

Time, Acceleration and Waiting, Andrew Root, For the Life of the World podcast, Yale Center for Faith & Culture.

Sarah Schnitker, Associate Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Baylor University, says we can all become more patient with practice. Start with noticing when and how you become impatient, she says. This will bring your impatience into greater awareness, where you can work on it. Practice every day: shopping, commuting, chores, children, parents, colleagues and spouses will provide you with lots of great opportunities 😃.

When you do notice yourself becoming impatient, try transforming your irritation or frustration into something positive by reframing your experience of the situation. (Psychologists call this "cognitive reappraisal".) Washing the dishes used to irritate the hell out of me. Now, I look forward to the sensory pleasure of immersing my hands in hot, soapy water. Taking the trash up our long, steep drive is great physical exercise. And if all else fails, the asshole in front of me might just be a great opportunity to work on improving my patience.

Finally, says Professor Schnitker, identify the meaning in your suffering—a narrative that will support your goal of greater patience. For some people, religion provides this support. I work on my patience as an effort at taking greater responsibility for myself. When I am impatient, I emit frustration and anger, and this pollutes the world. When I drive like a dick, I see others driving dickishly in response. When I am patient, I can absorb and transform other people's psychic pollution. I make the world a tiny bit better.

There is suffering, said the Buddha, and there is a path towards ending it. That path is patience and we walk it in meditation. When we sit on a cushion, close our eyes and focus on the breath, we learn to overcome our resistance—to silence, to stillness, to doing nothing, to rest. After a while, sitting meditation can become physically uncomfortable—even painful—and we must learn to overcome our resistance to that, too.

If we walk the path for long enough, said the Buddha in the Diamond Sutra, even our patience will disappear. We will have no need for it, because resistance will not arise in us.

Your patience should not bear the mark of patience. If it does, you still have an attachment to patience. If you still have not relinquished patience, you cannot be truly patient. True patience is devoid of a mark of self, a mark of others, a mark of living beings, and a mark of a life. When the four marks are non-existent, what do you still have which can be patient?

Each week I explore a word that has touched my heart. Subscribe to get my newsletter every Sunday morning. You can also follow me on Medium, or on LinkedIn. Feel free to forward this to a friend, colleague, or loved one, or anyone you think might benefit from reading it.